Byl jsem narozen 10. srpna 1928. A do nedávna jsem měl dojem, že jsem i avantgardní. Šest neděl po narození mě naši odvezli na Slovensko do vesnice Haspruňka. Kde prožijeme dětství, tam jsme taky doma. Teď je můj domov v cizině, kam se nebudu vracet.

Byl jsem dítě přehnaně sensitivní, čichal k trávě, stodolám i vodním tůňkám. Nikdy jsem se nenaučil pravopis, počty ani chemii. V roce 1939 jsem se dozvěděl, že jsem Čech, to jest nepřítel slovenského lidu.

Po Češích šli židi. Viděl jsem, co dovede udělat člověk člověku a začal se mi hnusit rasismus. Na dům nám napsali "čechú von hamba im". Ztratil jsem kamarády a v Čechách jsem nové nehledal. Byl jsem stále sám a samota mě netížila. Byl jsem emigrantem v rodné zemi.

Semilsko byl kraj duchařů a mediánů. Bylo mi 12 let, když mi sousedka prorokovala, že budu malířem medijních obrazů. které vidí viset v muzejích po světě, že mě vidí stoupat po širokých schodech až nahoru, kde mně podávají ruku velcí zemřelí umělci. A za mnou stále jde starý člověk.

Na toho člověka jsem dlouho čekal. Bylo mi už třicet let, kdy za mě začala bojovat profesorka Naděžda Melníková-Papoušková. V roce 1958 zanesla moje grafiky do Hollaru na výstavu hostů. Byly přijaty. Podmínka členství byla, aby mě vzali 3x na výstavu hostů. Pak jsem teprve žádal o členství.

Když staří členové viděli mé suché jehly, prohlásili, že takové prase, co tiskne grafiku na kladívkové čtvrtky, nemůže být členem spolku Hollar. Malíř Ota Janeček na to prohlásil, že právě jedno takový čuně by tam mělo být a byl jsem přijat.

Profesorka Papoušková už tady není. A já se pomalu připravuju na to podání ruky tam nahoře na těch schodech.

Ale před tím jsem chodil na Akademii výtvarných umění, odkud mě vyhodil profesor Minář v roce 1947 a po roce mě přijal profesor Štipl na VŠ UPRUM. Tam jsem pokorně studoval a ilegálně maloval, aby to nikdo neviděl, jelikož že prej to bylo zvrhlé a deformované a nic to neříkalo pracujícím (prof. Mrkvička).

Miloval jsem přednášky profesora Pečírky a Spurného, kamarádil s asistentem Arsenem Pohribným a hlavně byl vděčný profesoru Štiplovi, že mě tam nechal a já šest let modeloval panáky. Bez potvrzení, že jsem studovanej, se tenkrát umění dělat nemohlo.

V roce 1954 škola skončila a já šel domů. Odstěhovat se z Prahy znamenalo uměleckou sebevraždu. Dělal jsem promítače, šoféra i ředitele Domu osvěty. Ale čím jsem byl, tím jsem byl nerad. Na volnou nohu jsem šel již jako šedesátiletý.

Mám za sebou moc samostatných výstav. Jsem zastoupen ve sklepech většiny galerií v Čechách. Vystavoval jsem ve všech státech Evropy.

Ilustroval jsem hodně knih, bibliografií a exlibrisů. Za svůj život jsem byl svědkem několika revolucí. A nebyly to jen revoluce politické. Všechno to bojování skončilo jako plácnutí dlaní o vodu. Zůstali jen mrtví a nenávist člověka k člověku. Tohle všechno formovalo můj názor na pokrok v umění.

Jsou malíři velkých orchestrů, fanfár a činelů a malíři houslí bez doprovodů. Já chtěl být vždycky tím druhým. Umění jsem nikdy nedělil na staré a nové. Jak se režimy střídaly, byl jsem někdy považován za nepřijatelně moderního, jindy za trapně konservativního.

Vždycky jsem se snažil, aby moje obrazy byly čitelné. Chci malovat kousek ticha v současném kultu ošklivosti. Nechci šokovat, abych na sebe upozornil. Maluju bezbranné lidi s citlivou duší. Nechci "rvát vášně na cucky a samé cáry", jak radí Hamlet hercům. Lidská tragedie je bílá, tichá, stojatá jak vody a bez konce.

Uvědomuji si to dnes, když začínám odčítat čas, jak to dělají na raketových základnách. Maluju oltáře útěchy. Touhu po smíření. Vono totiž není co objevovat. Jen chvíli postát, než přijde konec.

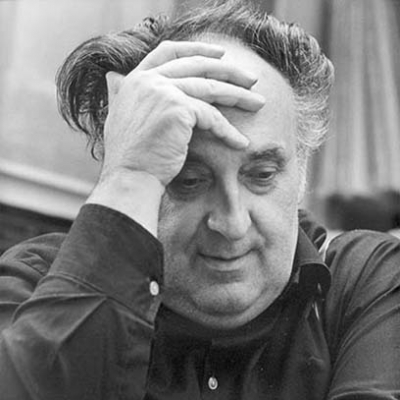

Vladimír Komárek |

|

I was born on 10 August 1928. Up until recently, I'd had the impression that I was also an avant-garde artist. Six weeks after birth, my parents took me to Slovakian village of Hasprunka. Where we spend our childhood is our home. Now, my home is abroad where I will not return.

I was much too sensitive as a child - smelling grass, barns and water ponds. I never learnt spelling, maths or chemistry. In 1939, I learnt I was a Czech, meaning the enemy of the Slovak people.

The Czechs were the target now, after the Jews. I saw what people could do to one another and racism disgusted me. They wrote ''Shame on the Czechs! Get out!'' on our house. I lost my friends and did not look for any in Bohemia. I was always alone but loneliness did not depress me. I was an immigrant in my own country.

The Semily region was a spiritual and sensuous land. I was twelve years old when our neighbour prophesied that I would become a painter of sensuous paintings she imagined hanging in museums all over the world. She saw me walking up a wide staircase right to the top where famous dead artists shook my hand. And behind me there always walked an old man.

I waited for that man for a long time. I was already thirty when Professor Nadezda Melnikova-Papouskova fought for my recognition. In 1958, she took graphics to the Hollar Club to show at a guests' exhibition. They were accepted. The condition for becoming a member was to have had ones art works exhibited three times as a guest. As soon as I had done that I asked to be admitted. When the old members saw my dry points they said that such a pig who prints graphic on hammered sheets could not be a member of the Hollar Club. Painter Ota Janecek then declared that one such pig should be there, and so I was accepted.

Professor Papouskova is not here any more. And I am slowly getting ready for the handshake up there on the stairs.

But before that I had been attending the Academy of Visual Arts, from which I was kicked out by Professor Minar in 1947. A year later Professor Stipl took me to the College of Applied Arts. I was painting for myself and humbly studying, but nobody saw my stuff because it was considered degenerate and deformed and had nothing to say to the working class (Prof. Mrkvicka).

I loved the seminars of Professors Pecirka and Spurny, was friends with assistant Arsen Pohribny and, above all, was thankful to Professor Stipl who let me mould statues for six years. Without a graduation certificate one could not officially create art.

In 1954, college ended and I went home. To move out of Prague was considered an artistic suicide. I worked in a projection room, as a driver and even as a director of the local free time Education Institution. But whatever I did, I did not like doing. I became a free lance artist in my sixties.

I have done many one-artist exhibitions . My artwoks are in the cellars and storage rooms of most of Czech art galleries. I have exhibited in all European states. I have illustrated a lot of books, bibliographies and ex-libris. Throughout my life I have witnessed a number of revolutions. And not just political ones. All that fighting ended like slapping the water's surface with the palm of the hand. Only the dead and human hatred remained. All this has formed my opinion of progress in art.

There are painters of large orchestras, flourishes and cymbals, and painters of violins without accompaniment. I have always wanted to be the latter. I have never divided art into old and new. As the regimes changed I was sometimes considered as unacceptably modern, other times as embarrassingly conservative.

I have always tried hard for llegibility of my paintings. I want to paint a piece of silence in the contemporary cult of hideousness. I do not wish to shock, to get attention. I paint defenseless and vulnerable people with sensitive souls. I do not wish to ''tear passions to pieces'' as Hamlet advises to actors. Human tragedy is white, silent, stagnant like waters, and endless.

I realise this today when I count down the seconds as they do at rocket launch pads. I paint altars of solace. Desire for reconciliation. There is nothing to discover, really. Just to stand here for a while before the end comes.

Vladimir Komarek |